The hotel only served breakfast from seven-thirty onwards, and we were down early, waiting to go into the dining room. The hotel proprietor was no more affable in the morning than he had been the previous day and did not hesitate to tell us that we were too early. But the breakfast when it came was good, setting us up well for the day. With some final adjustments of backpacks and boots, we were soon ready to go.

We left Chaudeyrac, going up the hill and back into the woods. We did not go back to where we had left the trail the day before, but instead took the direct route to Cheylard. That took us on a forest track initially, before joining a small road towards Cheylard. While walking on the road, a van came in the opposite direction, and the driver stopped, winding down the window to give us directions. Joff and I agreed that the driver looked remarkably like the hotel proprietor of the hotel in Chaudeyrac, but that he was much too good humoured to be the same person.

We did not go into Cheylard, but only passed the southern end of the village to take the forest road going southeast. Stevenson describes Cheylard as “a few broken ends of village, with no particular street,” though he does speak well of the inn where he stayed there. But we were not staying and went straight through the southern end of the village. Coming out of the village, we once again saw the lady that we had met in the gite in Pradelles. It is a feature of these long walks that one can meet someone, then not see them for days, and then meet them again. Most people walk at roughly the same pace, and though they may choose different places to stay, the nightly accommodations seem not to be too far apart.

The forest road out of Cheylard is all uphill, rising gradually by over a hundred metres. Along the way, we saw several parked cars, as well as people apparently wandering randomly in the forest. They all had carrier bags or wicker baskets, so it was clear that they were picking mushrooms. After the storm of the evening before, the night had been warm, giving exactly the right conditions for fungi to grow. We passed one group on the road, and they wished us “Bon route!” My French is limited, and I do not know the word for picking or foraging, so all I could say in reply was “Merci, et bon chasse!” Joff and I saw several fungi close to the route, but neither of us knows anything about mushrooms, so we could not say what might be edible and what might not. Besides, Joff reasoned, if they are close to the road and the pickers have not taken them, then they are probably not worth taking. Some, we knew, are definitely not for eating. The agarics, though beautiful, are dangerous.

After the ascent from Cheylard through the woods, there followed an immediate descent into a hollow, and another ascent on the other side. Stevenson describes his road between Cheylard and Luc as “Like the worst of the Scottish Highlands, only worse, cold, naked, and ignoble, scant of wood, scant of heather, scant of life.” But we found it not so. We touched the edge of the village of Espradels, but did not go in. The trail takes a sharp turn there, and we left it in our wake. The route goes back into the woods on a gentle road, continuing until there is a viewpoint overlooking the valley of Luc. Then the descent is rapid. Joff was slower than me on the descent, so I went ahead, agreeing that we should meet up in Luc.

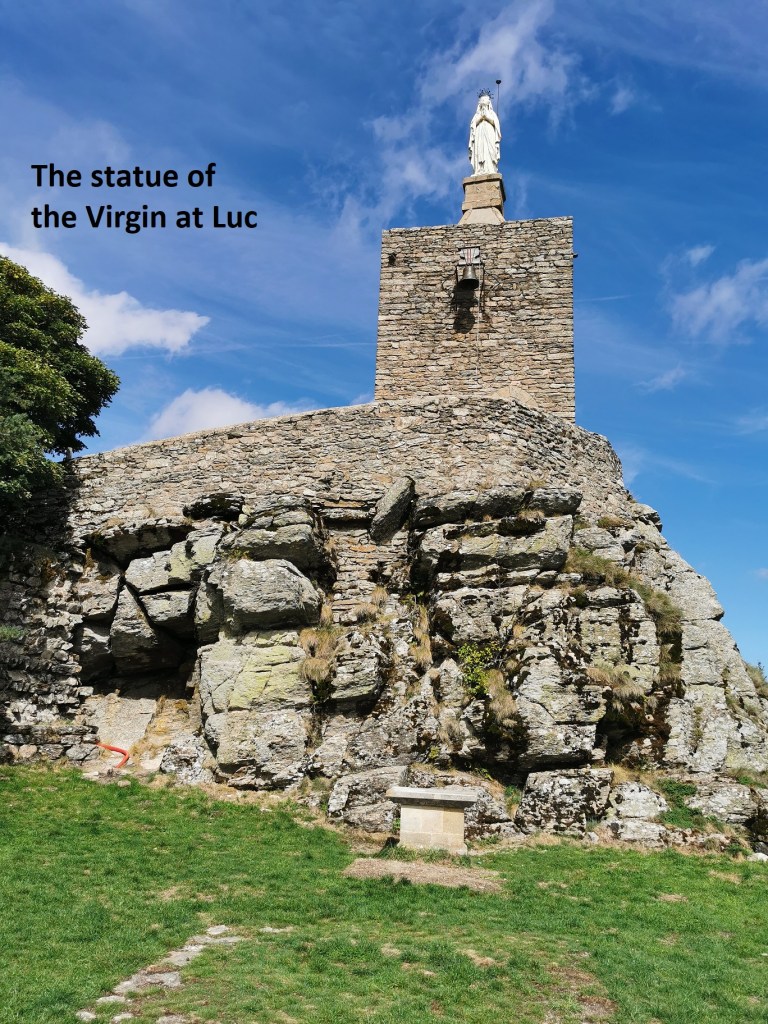

The first thing one comes to in Luc is the ruined chateau. Stevenson describes it as pricking up impudently below his feet, for one comes upon it suddenly. He notes that the ruin is topped by a large white statue of the Virgin, which was to be dedicated shortly after his arrival. While sign boards describe the castle and its parts, there is no indication as to the age of the statue, but based on Stevenson’s account, it must have been quite new when he passed that way.

While I was examining the castle ruins, Joff had gone on into Luc, and I met him at the first crossroads in the village. The app on the mobile phone indicated that we might find a restaurant both to north or south of that crossroads, and we chose north. Strangely, it was the right choice. We found no restaurant, but there was a small épicerie that provided to the needs of walkers. We got some bread, cheese, and cold beers. There are picnic tables in the village, and there we had our lunch en plein air. As we ate, we had a decision to make. My guidebook recommends a route circling northeast from Luc and coming back into the valley at the village of Laveyrune. Joff’s guidebook recommended a more direct and shorter route along the valley to Laveyrune. We decided to follow Joff’s book. As we ate and chatted, other walkers joined us at the picnic tables, all enjoying the lunch stop. But we still had quite a distance to go, so once lunch was over, we disposed of the rubbish leaving the site as if we and never been there, and hoisting the packs on our backs, we were on our way. In this, we differed from Stevenson, who spent the night at an inn in Luc.

Following the recommendations of Joff’s guidebook, we took the backroad out of Luc. As we went, it turned out that the restaurants supposed to be in the southern part of the village were a myth, so it was prudent that we had lunched as we did. The backroad soon joined the main road, which we followed for a short distance through Pranlac before turning into Laveyrune. Pranlac even had a mural of Stevenson and Modestine. An old stone bridge brought us to the other side of the Allier. Laveyrune is but a single street, and there was no one about other than fellow walkers as we passed through. One house had mushrooms drying in the sun, so there must be people living there.

After Laveyrune, the trail heads back into the hills. We were making for the Abbey of Notre-Dame-des-Neige, Our Lady of the Snows. Stevenson took a different route to the abbey, following the Allier river up to La Bastide and then turning eastwards to reach the abbey. Our route was more direct, though probably going through more difficult terrain. As the trail turns sharply near Serres, we took a wrong turn, losing the route, but then regaining it as we came close to Roggleton. Then we were into the Forêt Communale de Laveyrune, reaching the top of this section at 1225m. It is a desolate forest, and uninviting, but this was our route so go we must. The route flattens out after that, and after a time we came to the ruins of the original abbey.

The Abbey of Notre-Dame-des-Neiges was a Trappist monastery. The Trappists are a branch of the Cistercian order of monks. The abbey was founded in 1850, and was well established when Stevenson visited in 1878. However, the original monastery was destroyed in a fire in 1912, after which a new monastery was built further along the road to La Bastide. I would have liked to have stayed in the old monastery as Stevenson did. The place is central to his narrative, with an entire chapter of the book devoted to his time there, and he outlines in detail his discussions with the monks and the other guests there. One note in particular strikes a chord. He writes that in those times, “you cannot say anything to a man with which he does not agree, but he flies up at you in a temper.” If he were writing today, he might add that as well as being physically attacked, you might also be denigrated on social media.

We stopped at the ruins of the old abbey, where a stone plaque records its founding and its destruction. As we looked over the site, we could see a figure coming toward us along the track. From the distance, they looked like a priest, dressed in black robes. As we went on, we expected to meet the person, but we never saw them again. Joff and I both remarked that perhaps it was a ghost of some long dead monk of the monastery, though I am sure there is a more rational explanation.

The trail descends slowly from there to where the new monastery stands, that is if a building from the early twentieth century can be called new. The abbey itself does not take guests, but there is an accommodation building very close by. With falling numbers of vocations in the more recent decades, the new abbey reached a crisis point in 2021. Two of the older monks died, leaving only ten monks remaining, all of them of considerable age. The abbey was handed over to a group of Cistercian nuns, so that today, one sees no monks, but just occasionally nuns going about the grounds. Even the accommodation building seems underused, with space for many more people than were staying there when we visited.

As we arrived at the abbey, we met a trio of ladies who were making the journey with a donkey. We had seen many places with donkey manure on the trail, so we knew that some walkers must include a donkey in their group, but this was the first we had actually seen doing so. We asked how was it with the donkey, and they replied that it was very difficult. Sometimes she would stop to eat the grass along the edge of the trail, they told us, and once, she simply lay down in the middle of the road and refused to go on. Truly, the descendants of Stevenson’s Modestine are no better than she was. Joff suggested that they should have a goad, as Stevenson did. They looked at Joff with something like puzzlement. The methods used by Stevenson, and his treatment of Modestine, would get you arrested for animal cruelty in modern times. And probably rightly so.

Dinner at the monastery was a pleasant affair. There was plain food, but plenty of it, and we were well restored by the meal. Sadly, the language barrier prevented us from fully engaging in conversation with our fellow travellers. All were French, and our limited vocabulary in that language did not allow for an easy conversation. The guests are expected to wash up after dinner, and truly, many hands make light work. In almost no time, the crockery was washed, and the tables cleaned to be ready for breakfast on the morrow.

And with that, it was time to turn in and get some sleep to be ready for another day of walking on the morrow.